পুনরায় / Punaray: A Return to Process

June 2025- January 2026

At Brihatta, we believe creativity exists in the unseen—moving

through time, language, and tradition. It does not seek repetition, but

renewal.

পুনরায় | Punaray (Anew) is an invitation to reimagine familiar forms with new perspectives, to pause and listen before acting, and to embrace practice as an ongoing dialogue. Running across eight months, পুনরায় | Punaray brings together artists, architects, craftsmen, and researchers in residence at Brihatta. The programme emphasizes collaboration and exchange, where ideas, materials, and people meet and evolve through shared processes of making.

Through painting, weaving, assemblage, and collective experimentation, পুনরায় | Punaray searches for new possibilities of seeing—rooted in everyday life, yet open to the transformative horizons of what art may become.

Talk 01: Weaving Resistance: Textile, Memory, and Feminist Storytelling in Bangladeshi Contemporary Art by Kashfia Arif

July 2025

Kashfia Arif, in her research paper, positions textile as an active, mobile force that carries stories, bodies and resistance across time and space. She discusses the textile-based works of 3 Bangladeshi artists: Tasleema Alam, Najmun Nahar Keya and Yasmin Jahan Nupur, and how they use textile not only as a tangible medium, but as a methodology that connects past and present. Kashfia discusses the textile-based work of three female Bangladeshi artists: Tasleema Alam, Najmun Nahar Keya, and Yasmin Jahan Nupur, bringing their distinct, yet interconnected, practices together to explore how each artist mobilises textile as a medium of resistance, continuity, and transformation, translating past knowledge for the present.

Alam’s Symbols of Power, created in collaboration with Jamdani artisans, reimagines heritage motifs within one of Bangladesh’s most iconic textile traditions. Guided by the principle that “tradition is new ways of doing old things,” she positions Jamdani not as a static heritage, but as a living form of cultural endurance.

Keya’s The Spell Song translates Khona’s bochon (folk proverbs composed by the medieval astrologer) into a text-based sot sculpture, created from Tangail sarees, reviving feminist knowledge through voice, language, and material.

Nupur’s participatory performance Let Me Get You a Nice Cup of Tea invites viewers to share tea and stories, seated around a table mapped with textile representations of colonial trade routes—foregrounding the enduring impact of empire on everyday rituals and identities.

Through practices of weaving, stitching, and storytelling, these artists use textile not only as a medium, but as a methodology: erasing erasure, translating memory, and stitching together alternate futures and world-making. They create transformative affective archives that connect past and present, oral and material culture, body and land, and the individual and collective. By braiding their work into a single narrative, Kashfia positions textile as an active, mobile force—a carrier of stories, bodies, and resistance across time and space.

Kashfia Arif is a cultural scholar, curator, writer, and editor. She is currently

pursuing her PhD in Theory and Criticism at Western University, Canada,

researching absurdism and creative practices in contemporary visual culture.

Talk 02 : Memory, Migration and Adaptation of Katan weavers of Mirpur by Farzana Yusuf and Saifur Rahman

July 2025

Farzana Yusuf and Saifur Rahman delve into migration history, skill transmission - and its silent transformation- of Mirpur Katan, a craft currently in decline. With relocation, artisanal processes are inevitably reshaped, adapting to new environments and circumstances. This quiet yet significant movement not only carries with it the tangible aspects of craftsmanship, but also the intangible history embedded within the fabric of Katan. Saifur and Farzana examine the historical trajectory and cultural adaptation of the Katan weaving community in Mirpur, Dhaka, focusing on the socio-material implications of pre- and post-Partition migration from Varanasi. Drawing from firsthand interviews, observations, ethnographic fieldwork, and textile material and process analysis, they investigate how stories of generational memory and adaptation are embedded in the processes of making, and how displacement has reshaped not only the individual and collective identities but also the craft of their forefathers.

Their study unpacks how these

processes have evolved in response to constraints of the new environment, shifting

market demands, and generational knowledge transfer. It situates the evolution

of the Mirpur Katan saree within a broader framework of urbanization,

marginality, and intangible cultural heritage, and argues that the weaving practices

of this community represent more than artisanal continuity; they constitute

acts of resilience and re-invention that negotiate belonging in the face of spatial

and cultural rupture. The research contributes to scholarship on migration-affected

crat ecologies, diasporic cultural production, and the politics of heritage in

South Asia.

Farzana Yusuf is an impact

strategist and a researcher working at the intersection of sustainability,

entrepreneurship, and textile design. A member of the Executive

Committee of the National Crafts Council of Bangladesh (NCCB) and an advisor at

Women Forward International (WFI) in Washington, DC, Farzana continues to

advocate for sustainable, culturally rooted design practices.

Sk. Saifur Rahman is a multifaceted

professional whose work spans journalism, fashion, and cultural preservation. A

senior journalist and former Deputy Editor of Prothom Alo, he is also an executive

committee member and former General Secretary of the National Crats Council of

Bangladesh (NCCB), and has contributed to numerous publications both nationally

and internationally.

Traces of Us: A Collaborative Art Encounter || An art workshop by Artist Ioana Palamar

July 2025

The workshop explored the idea of recycling fragments from our unconscious—retrieving buried images, sensations, and memories, and bringing them into the light of conscious awareness. The process began with reflecting on a deeply personal experience, whether comfortable or unsettling, that has left a lasting imprint.

The

workshop explored the idea of recycling fragments from our

unconscious—retrieving buried images, sensations, and memories, and bringing

them into the light of conscious awareness. The process began with reflecting

on a deeply personal experience, whether comfortable or unsettling, that has

left a lasting imprint.

Through this introspection, each artistic gesture became an act of transformation. Drawing and colour were deliberately linked to specific emotions or personal memories, so that every line, shade, and texture acted as a bridge between the inner world and the external artwork. A strong emphasis was placed on the sensorial dimension of creation, particularly the tactile experience—feeling the texture of the paint, the resistance of the surface, the physical presence of colour. This haptic connection reinforced the intimate relationship between artist and medium, enabling a deeper embodiment of the emotional and psychological states being explored. In the first phase, participants collaborated on a large-scale collective drawing on a long roll of paper. They then painted eyes or portraits on unconventional objects, such as plastic bottles, which were later assembled into a collective installation.

Conceived as a form of scenography, the installation incorporated spotlights, transforming the space into a play of light and shadow, where the painted objects themselves became the actors on stage.

Programme Note

My

work explores personal memories rooted in childhood, whose influence persists

like hidden roots in the unconscious, waiting to surface into awareness.

Inspired by Alejandro Jodorowsky and Marianne Costa’s Metagenealogy, as well as

Freud’s and Jung’s theories on the unconscious and collective memory, the

artworks address inherited patterns, intergenerational trauma, and the human

search for self beyond imposed identities.

My paintings focus on human vulnerability in all its dimensions—psychological, cultural, historical, and philosophical—symbolised by the image of flesh (Flayed series of artworks). This unsettling metaphor provokes viewers to question the realism and meaning of the imagery. The initial reaction of discomfort acts as a threshold, inviting deeper reflection on consciousness and shared human experience. Material details are rendered with such precision that they create visual tension, pushing the viewers beyond their comfort zone. Each object is unique in form and dimension, conceived as a rebellion against rigid social order and a metaphorical act of breaking invisible constraints. This liberation—breathing beyond societal masks—reveals the essence of being.

Some

of my artworks (Memories, Back to past, Layers of soul series of artworks)

translate inner tensions into unconventional mixed techniques, embedding

emotional and psychological depth into the materiality of the works. Recurrent

motifs such as eyes and distorted portraits embody moments of solitude,

introspection, and moral deformation, ultimately striving for a sense of

spiritual balance visible in the palette, technique, and process.

Ioana Palamar

Artist

পদ্ম / PODDO - LOTUS

August 2025

This series is part of

artist Bishwajit Goswami’s ongoing art research project, হাজারীবাগ / Hazaribagh (A Thousand Gardens)—a

multidisciplinary exploration of reconnection through memory and

transformation. Goswami, through his travels, examines Hazaribagh as a

contested landscape shaped by histories of displacement and movement often

challenging human capacity for renewal. পদ্ম / PODDO centers

on the resilience of migrant women who have resettled in Old Dhaka after losing

their homes to natural disasters and economic hardship in different parts of

Bangladesh. These women, now engaged in the informal plastic recycling trade

along the Buriganga River, have forged paths of survival and self-empowerment

through waste picking and sorting. Their labor—often invisible, yet

indispensable—speaks to broader themes of sustainability and the power of

collective adaptation.

Goswami’s mixed-media

works incorporate recycled materials, archival photographs, found objects, and

natural earth elements, executed on wooden panels and resin. The pieces mirror

processes of layering and preservation where each object, like each life,

carries an imprint of the past with a possibility of transformation for the

future.

Commissioned and collected by Brihatta Art Foundation

Letter to the Lotus: Imaging, Not Imagining, a Conversation

By Ahmed Tahsin Shams

Dear Lotus,

I am

writing this letter to you because I have realized I want to learn how to be a

gem amid dross, as you rise from mud without denying the mud. I am in love with

your transformation technique. Teach me.

Lotus: Why?

What troubles you?

ATS: In the age of climate crises, our

screens, cameras, technical tools, and servers are not neutral but complicit in

the crime if there is a court for climate justice. They are dug from the same

earth my film claims to defend. I work inside that compromise. I want that discomfort

to teach me.

Lotus: What

will you learn first?

ATS: To stop spectating and start

witnessing. Spectating asks for clean views and quick meaning, like

advertisements, but witnessing stays with bodies, matters, textures, and time.

It does not rush to fix. It listens. It stays with the trouble, it celebrates

the discomfort. It uses all the senses to preserve the experience in the

memory. Let me rewire the sensory patterns: witnessing with ears and listening

with eyes can transform the audience into an artist.

Lotus:

Where did you learn to listen with eyes and see with ears?

ATS: At the Brihatta Art Foundation, I

find the space functioning as a medium to introduce a different lens for seeing

Hazaribagh, Dhaka, by the Buriganga River. I met climate migrants (women) who

sort plastic for a living. Their hands map the city’s afterlife. They showed me

how survival is created from waste, how care can begin with a pile of scraps.

At Brihatta, I learned that art can be a place where industry and hope

intersect without giving the illusion of comfort and redemption.

Lotus:

Without the “illusion of redemption”? How?

ATS: The action of saving or being saved

from sin is the literal meaning of redemption, which is the core ground of

religion. Art exceeds this concept and decenters authorship. Brihatta, as a

space, showed me what collaborative art with multispecies authorship is, beyond

human mastery, but shared inquiry. To me, the action of saving is less

important than the action of responding. I will get back to it later.

To speak of

“how,” I can start by naming the tools, the mediums, the vessels. Contrary to

the commodity aesthetics [of the bourgeoisie] that hides the process, Brihatta

reveals it. I get to ‘sense’ the ‘matters’ (not

only see). Yes, materiality matters. It inspired me to think of… if I can name

the tools, make them visible in my art: metals and watts in my filmmaking

process, if I can keep the glare that burns the image and the wind that ruins

the sound, there I may encounter a counter pedagogy and an anarchive: not a

vault that closes, not a top-down teaching method, but a living bundle of

traces that stays open to weather and error.

Lotus: Why

honor error?

ATS: Error is evidence of a relation. Not

every wound heals. We must accept nature’s duality. Fire destroys and also

enables making. The lotus-in-muck figure fits (Bangla: gobor-ey poddophul):

beauty emerges from contamination without pretending the muck is gone. If I

keep the window open, I will also get dust, bacteria, and viruses, along with

summer sunshine and autumn breeze. These are two sides of one coin. I can’t

expect only one side to be correct. I should accept the storm, too.

Coming back

to your question of “error,” I won’t say it’s honoring or not; I would rather

say it’s an action. As promised earlier, to define action: here, it is not a

promise to heal everything, but it is “response-ability,” as Donna Haraway puts

it [not responsibility]. The only way to be able to respond to any species,

matter, human, or nonhuman is to learn to communicate. There comes the creative

arts. If science excels in discoveries and innovations, the creative arts

provide it with a medium —the body —to communicate with the world and other

species.

Lotus: What

kind of space can hold that conversation?

ATS: Brihatta has already done that and

continues to do so. New visitors to this space in Hazaribagh should consider

the following questions: How does this space affect your body? How does it

shape time and space for you? As a visitor, it taught my body to respond to art

by listening with my eyes!

Lotus: So,

how do you plan to hold on to that inspiration?

ATS: Bishwajit Goswami’s project

Poddo [Lotus, 2025] reveals how contamination can be a

teacher, human limits can be forms, slowness can be a method, and shared

authorship can be a practice. Here comes our film Lotus in the Wasteland. I

wish to film with “the world,” not about the world. I wish to craft a pedagogy

of collaborative art through this film, undoubtedly inspired by Poddo.

Lotus: When

shall we meet again?

ATS: We will be meeting soon—where the

city’s waste meets the river’s breath, either in the form of these bodies we

hold on to for now or on the elemental bridge—in the form of the air, dust, and

soil/mud.

—ATS

Ahmed Tahsin Shams

Filmmaker, Author, Graduate Researcher, and

Associate Instructor, Cinema Studies,

Media Arts and Sciences, Indiana University Bloomington, USA;

Former instructor at the University of Chicago, Illinois,

and Notre Dame University, Indiana, USA.

Material Encounters with Bishwajit Goswami

August, 2025

An open, participatory space that allows

for shaping, assembling, and reimagining. The activities echo core themes of

reuse, adaptation, and collective creativity found in Goswami’s recently

commissioned series পদ্ম / PODDO

(LOTUS) by Brihatta Art Foundation.

Highlighting the stories of informal waste workers who form a vital- yet

invisible- part of the plastic recycling industry in Old Dhaka, Material Encounters

offers an intimate way to connect with Artist Bishwajit Goswami’s পদ্ম / PODDO (LOTUS) series and the communities it honours.

Participants were invited to experience art as a bridge between conversation

and creation at Brihatta Art Space, Hazaribagh, through an artist talk, guided

tour, and hands-on material encounter.

A Narration by Amrita Bhadra

A Narration by Amrita Bhadra (Participant,

Material Encounters)

Department of English and Humanities

University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB)

From the womb of the river,

A goddess appears;

to bless and curse,

And delve into her mighty power.

These fragile humans

exude reverence

For the destroyer

and the Creator.

A celebration of life;

A continuation.

In the creation of this line or a flow of phrases, is from the experience I

had today at Brihatta Art Foundation. When I came here and I saw the artist

himself speak about পদ্ম / PODDO. It reminded

me of how from the mud the পদ্ম / PODDO blooms. পদ্ম / PODDO is a

symbol of a goddess. With water there comes creation. It is also this water

(the same water) that destroys. We see these women shifting lives; the same

woman who harvests is the same woman who works with garbage. This was the

inspiration behind the artwork.

It has been a memorable day; one of those days which transforms

us.

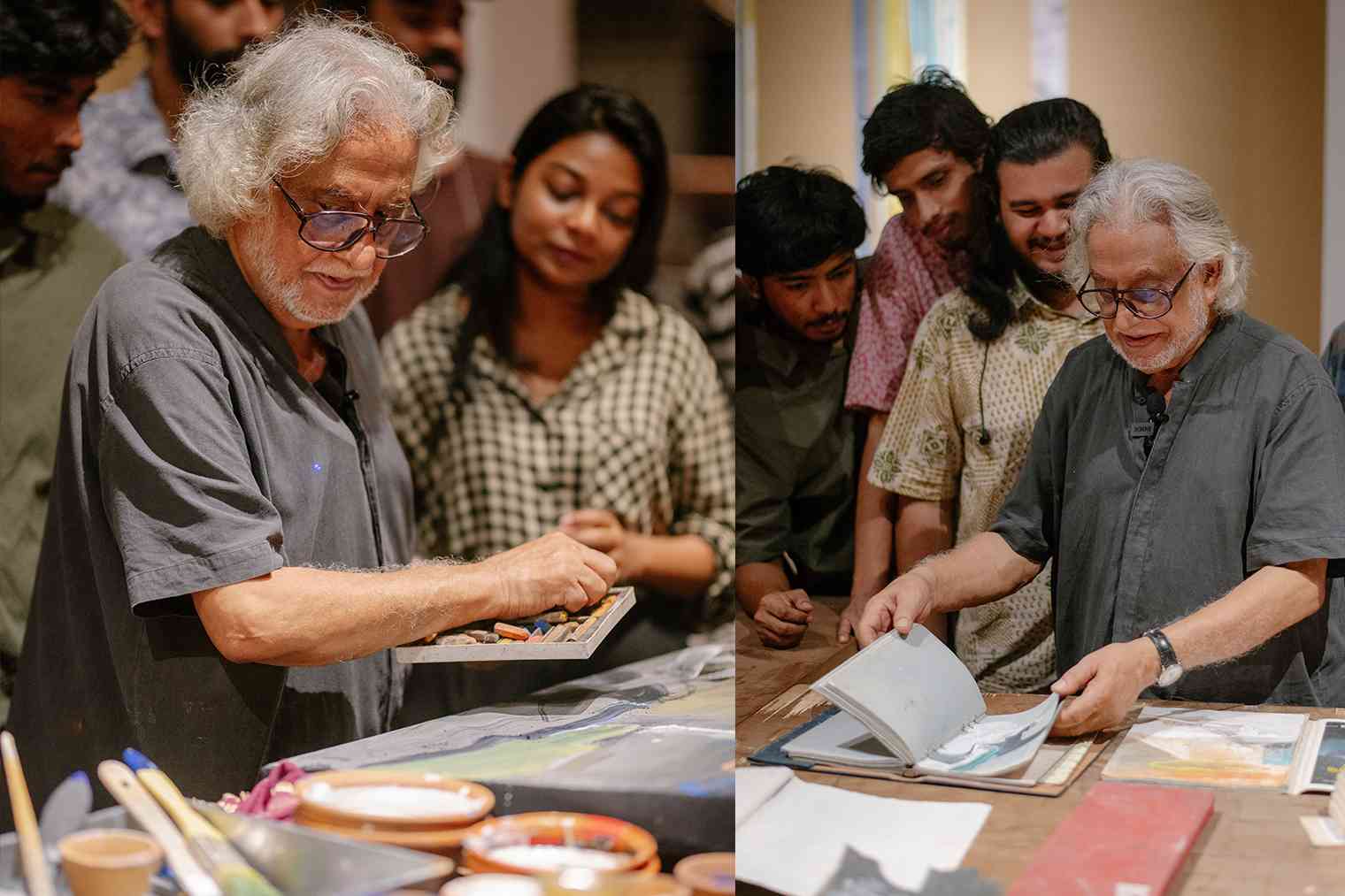

মনির _পুনঃসংযোগ : An Afternoon with Artist Monirul Islam

October 2025

Honoring

the child’s mind within us opens pathways to art that is courageous and deeply rooted,

in both self and place.

By

cultivating this practice, how does an artist come full circle — to leave,

explore, and ultimately find a way back to their roots, both physically and

spiritually?

“মনির_পুনঃসংযোগ : An Afternoon with Artist

Monirul Islam”,

weaves together personal narratives, meaningful conversation, and spontaneous

creative exchange between the artist himself and participants seeking to deepen

their connections with spaces that surround them.

Artist Monirul Islam bio

Monirul

Islam

b. 1943, Chandpur, lives and works in Dhaka and Madrid

Monirul

Islam is known for his constant search for new methods of painting and

print-making. Organic methodologies carry a lot of weight in his artistic

process and he makes his own paint and paper as part of his practice. His

techniques and devotion to the craft propels him to find materials and pigments

from his surroundings, and use elements in unconventional ways and scenarios.

Islam

completed his studies at the East Pakistan College of Arts and Crafts, Dacca in

1966. He was a teacher at the same college from 1966-1969 and left teaching for

higher studies in Spain, studying mural paintings at the Madrid Academy of Fine

Arts. Even while abroad, he remained in touch with Bangladeshi artists and

conducted workshops when visiting Dhaka in order to pass down his

methodologies, making him one of the most influential living artists currently

in Bangladesh

For

his esteemed accomplishments in art, he received two of Spain's top civilian

honors: the Cross of Officer of the Order of Queen Isabella (2010), and the

Commander Spanish Order of Merit (2018), and Bangladesh Government's civilian

award Ekushey Padak in 1999.

Programme Note

I

have known Artist Monirul Islam for nearly two decades — as both a remarkable

creator and a person of rare humility. Having worked on several projects

featuring his works, I have come to understand not only his mastery of form and

material but also the depth of his artistic philosophy. To comment on an artist

of such stature is never easy. Monirul Islam’s practice transcends conventional

categories — his art embodies silence, spirituality, and a timeless dialogue

between man and nature.

During

the Brihatta session, what impressed me most was the atmosphere he created

around him. Young learners listened with deep concentration and quiet reverence

— a scene that echoed the traditional ‘Guru–Shishya Parampara’ rather than the

formal detachment of the Western white-cube model. The session felt alive,

fluid, and human — an open dialogue rather than a lecture.

His

generosity in sharing knowledge went far beyond style or geography. He spoke

effortlessly about materials, techniques, and the philosophy of picture-making,

inspiring those around him through both thought and demonstration. I have

always admired his ability to express profound truths in simple words — especially

his belief that an artist’s true connection lies between nature and society.

I

found my connection in his words. Having spoken with him on several occasions,

even during personal visits to his home, I am always reminded of his humility

and sincerity. He once told me, and repeated on the day for all “Some artworks are for galleries, for sale —

but some are personal; I will never show them to anyone.” That statement

encapsulates the essence of Monirul Islam — an artist guided not by the market,

but by an unwavering devotion to inner truth and sincerity.

Bipul Mallick

Visual artist & Educator

Trustee Brihatta Art Foundation

Talk 03: গঙ্গাবুড়ি / Gangaburi & River Chants

October 2025

RIVER CHANTS is a multidisciplinary project at the intersections of climate change and migration, shifting the narrative from those who leave to those who remain. It explores these global challenges through folk songs tied to waterways, emphasising women, who often preserve these musical traditions and are less likely to migrate. It observes these phenomena through a “sonic and poetic hydrology,” where water is an element for connection.

Led

by artist Giuditta Vendrame and director Ana Shametaj, the project draws on the

academic expertise of Bishawjit Mallick (climate change and migration),

Costanza Sartoris (feminist new materialism), Radha Kapuria and Priyanka Basu

(ecomusicology).

RIVER

CHANTS is a research project granted by Creatività Contemporanea of the Italian

Ministry of Culture – MiC under the Italian Council program (2024) and Stimuleringsfonds.

The

‘গঙ্গাবুড়ি / Gangaburi’ River

Heritage Project was launched in 2023 by Brihatta Art Foundation, with support

from the EUNIC Bangladesh cluster, including Alliance Française de Dhaka, British

Council, Goethe-Institut Bangladesh, the EU Delegation in Bangladesh, the

Embassy of Italy in Bangladesh, and the Embassy of Spain in Bangladesh. The

second phase, initiated in 2024, was supported by British Council Bangladesh.

The

title of this project is inspired by the song “Gangaburi” by Kafil Ahmed.

Programme Note

পুনরায় / Punaray Talk 03 brought

together two projects – River

Chants

and Gangaburi; in their

own ways, with an attempt to listen to the river not as landscape, but as a

living archive of emotion, memory, and belonging.

In

a time when environmental discourse often centres on catastrophe, these

projects offer something quieter yet deeply rooted within. Both River Chants

and Gangaburi turn away from distant observation and lean toward closeness in

an approach shaped by listening, sensing, and being together.

The

‘river’ here is not a backdrop; it’s a participant, a co-narrator.

In

River Chants, artist and researcher Giuditta Vendrame and her collaborators

approach the river through sound; what she calls a “sonic and poetic

hydrology.” They listen to the voices of women who remain in climate-affected

regions, women whose songs and memories flow like tributaries of resilience.

Here, listening itself becomes a form of research practice that treats water as

a living narrator, dissolving the boundaries between human and environment, body

and current, voice and echo.

Gangaburi

approaches the Buriganga through visual and material languages: painting,

photography, sculpture, installation, and collective storytelling. It connects

artists and communities around the river to reimagine its presence not only as

a site of loss, but also as a space of reconnection. Through this

collaboration, Gangaburi restores the river’s presence within contemporary

consciousness; transforming its polluted, neglected body into a site of reflection,

empathy, and renewal.

If

River Chants gives voice to those ‘who’ remain, Gangaburi gives form to ‘what’

remains.

পুনরায় / Punaray Talk 03

ultimately delved into the finding that both River Chants and Gangaburi are not

simply about rivers, they are about ways of being in relation. About belonging,

endurance, and the fragile beauty of staying connected – to a place, to a

community, to an ecosystem that sustains us even when we fail to sustain it.

They show us that engaging with a river is also engaging with time.

We see what flows, what

stays, and what returns.

Souradeep Dasgupta

Researcher

Brihatta Art Foundation